What Big Ag Stole:

Reclaiming Heritage Dexter Breeding Practices

by Michelle Parsley, M.Photog., M.Artist, Cr.

Hero image: “Melkkarussell (Rotary Milking Parlor)” by Bjørn Erik Pedersen, used under CC BY-SA 4.0. Cropped and color-modified for tone consistency.

Big Ag didn’t invent the concept of data-driven farming —

It borrowed what small farmers already knew, then forgot why it mattered.

I’m well aware that, as a nation, we couldn’t feed ourselves today without large-scale agriculture. This isn’t a jab at commercial farmers — it’s a reminder that heritage breeders first developed the very principles Big Ag was built on.

For centuries, heritage farmers and small-breed stewards have tracked, tested, and refined their herds with purpose and integrity. They did it with notebooks, ledgers, and milk pails instead of digital scales and spreadsheets — but the heart behind the work was the same.

The difference was never the how. It was the why.

Heritage Dexter breeders recorded milk weights, calving intervals, and temperament to preserve and improve. Big Ag turned that system inside out, valuing profit over stewardship. Somewhere along the line, efficiency replaced care, and the quiet wisdom of small farms was buried under yield charts and quarterly goals.

It’s time to reclaim the original intent behind good record-keeping and selective breeding — not to chase numbers, but to honor what those numbers mean — and to guide the future of the Dexter breed with real data instead of the ambiguous recollections that all too often pass for truth.

Before “Big Dairy” — The Origins of Record-Keeping

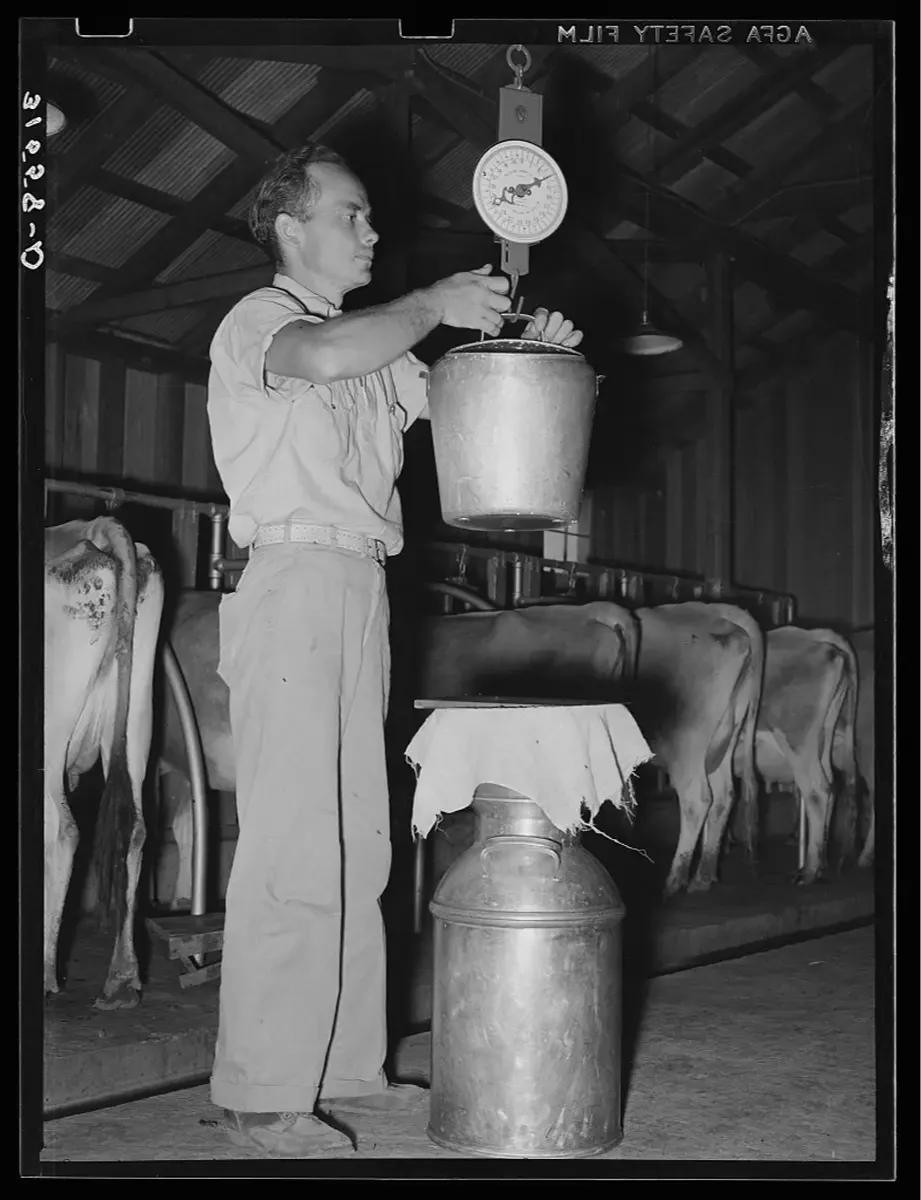

Image: Dairy farmer recording milk weights by hand, Escanaba, Michigan, 1940. Photograph by John Vachon, Farm Security Administration, Library of Congress. Public Domain – U.S. Government work.

Long before there were spreadsheets and software, good farmers were already scientists. They wrote in ledgers, marked dates on barn walls, and compared milk by the pail.

Heritage Dexter breeders have always kept careful notes: milk weights, calving intervals, conformation, and temperament. Those records weren’t paperwork; they were lifelines — the only way to know which animals were truly improving the herd.

By the mid-1800s, herd books and stud registries began to appear across Britain and America. Families guarded those books as heirlooms, passing down not just bloodlines but judgment — which pairings worked, which didn’t, and what each cow brought to the table.

Paper trails built bloodlines long before spreadsheets existed.

Before industrialization, milk was measured by volume — a bucket here, a quart there — and written in the margin of a feed ledger. Those rough notes were never primitive; they reflected the tools and priorities of the time. When farm scales became affordable, breeders simply sharpened the lens. Precision didn’t replace tradition — it refined it.

Today’s digital meters and mobile apps serve the same purpose as those ink-stained pages: helping honest stockmen make wiser decisions. Whether you use a chalkboard or a cloud backup, the principle hasn’t changed — pay attention, write it down, and learn from what you see.

Measuring Matters — Whatever the Method

Pre-industrial farmers didn’t need electronics to understand their animals. They measured by sight, sound, and feel — by the splash in a bucket, the heft of a calf, or the frame of a cow standing in the morning light. Long before digital readouts, those simple measures told them all they needed to know.

The point was never perfection — it was consistency.

Every farmer who noted Dexter milk yield, body condition, height, or calving intervals was building a picture of the herd one line at a time. Those daily details revealed which cows milked steadily, which grew well, which calved easily, and which passed on the right balance of thrift and temperament.

Modern tools simply make it easier to see what good farmers have always noticed.

A digital scale, a weight tape, a milk-tracking app, or a spreadsheet adds precision, but it doesn’t change the purpose. What matters isn’t the device — it’s the discipline.

Memory lies. Data doesn’t.

Record-keeping doesn’t have to be complicated. A marked pail for volume of milk, a measuring stick for height, a weight tape measurement documented with a quick note on a phone will teach you more than memory ever could.

Patterns emerge. Decisions get easier.

Whether you measure by volume, weight, or height, if you write it in ink or type it in code — consistent record keeping of each animal creates clarity, not complexity.

Measuring milk by volume was a time-honored method long before digital scales — each filled pail or can told its own story of the morning’s yield.

Public Domain image, Library of Congress (Farm Security Administration Collection)

The Purpose Behind the Numbers

Today, Big Ag measures for efficiency and profits above all.

Historically, heritage breeders measured for stewardship and improvement.

For those early farmers — and for heritage Dexter breeders today — the why was never profit. It was understanding.

They studied Dexter milk weights, calving intervals, and butterfat to strengthen their herds generation by generation. Every number represented a living creature, not a statistic. Data was a tool for discernment and stewardship — not domination.

That same principle guides my work now. I track daily milk weights, calving intervals, height, growth rates, and thrift — not to squeeze more from a cow, but to see her clearly. Those numbers help me decide when to rest her, when to breed her, and which pairings create a more balanced Dexter for the future.

Data isn’t the enemy.

Data for profit can become one if used without wisdom.

And breeding without data? That’s not intuitive — that’s reckless.

When record-keeping serves stewardship instead of spreadsheets, the numbers regain their original purpose: a quiet language of care that helps farmers make better decisions, not bigger ones.

Dexter Stewardship Through Selection

Heritage breeding was never random.

Every Dexter pairing reflected a careful balance between what to keep and what to change — and the knowledge to make those decisions came from records.

Early Dexter farmers didn’t breed for the biggest udder, the highest milk yield, or the flashiest bull. They bred for function — cows that lived long, raised strong Dexter calves, and gave milk rich enough to nourish a family and beef that filled the smokehouse each winter. They understood that every generation offered a choice: improve the line, or weaken it.

That’s the philosophy I follow today. I look beyond the milk pail to the whole animal — her temperament, handling, longevity, udder structure, carcass balance, and the calves she produces. I keep data on milk weights, calving intervals, and growth rates, but I also watch her eyes, her stance, and her patience in the stanchion. Balance among the most desirable traits is the goal.

Each of those interconnected details tells the truth about a Dexter’s usefulness and worth. Without records, how would I know?

Record-keeping is not sentimentality.

Record-keeping is not imitation of industrial farming.

Record-keeping is not an exercise in needless complexity added to already full lives.

Record-keeping is the essence of stewardship — quiet, deliberate, and rooted in respect for the animals entrusted to us.

Selective breeding, done thoughtfully, honors both the animal and the future of the Dexter breed. The goal isn’t to create perfect cows — if we’re being honest, there’s really no such thing as a perfect cow. The goal is to create sound animals: balanced between milk and beef, gentle, and built to serve families for years to come.

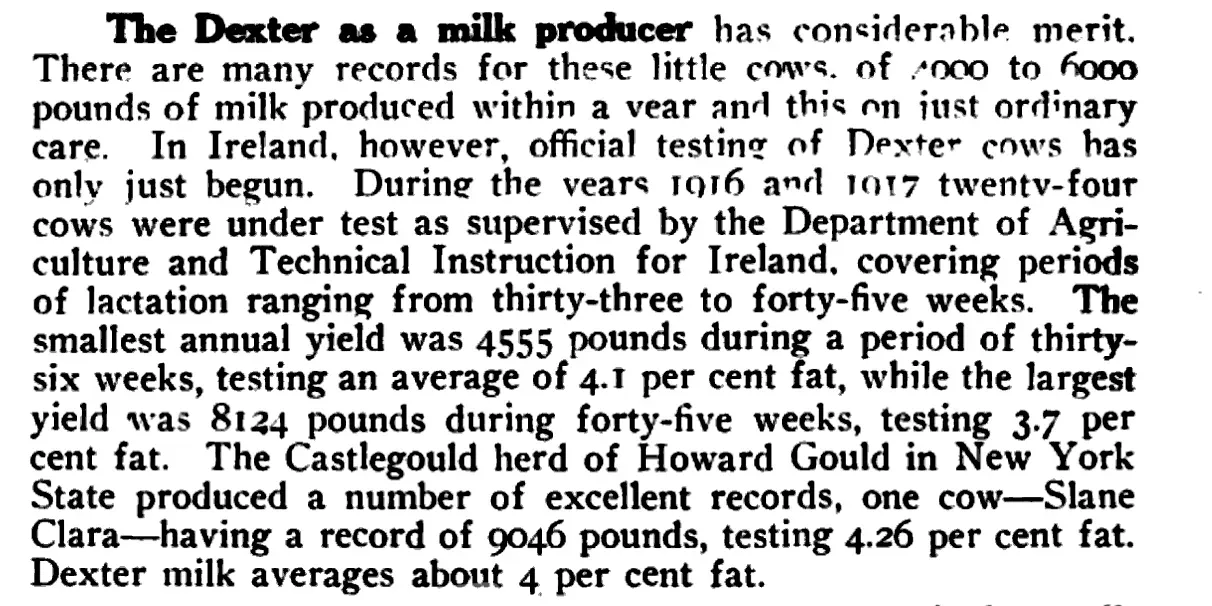

Historical Record: Irish Milk Tests (1916–1917)

“The Dexter as a milk producer has considerable merit. There are many records for these little cows, of 4000 to 6000 pounds of milk produced within a year and this on just ordinary care. In Ireland, however, official testing of Dexter cows has only just begun. During the years 1916 and 1917, twenty-four cows were under test as supervised by the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction for Ireland, covering periods of lactation ranging from thirty-three to forty-five weeks. The smallest annual yield was 4555 pounds during a period of thirty-six weeks, testing an average of 4.1 percent fat, while the largest yield was 8124 pounds during forty-five weeks, testing 3.7 percent fat. The Castlegould herd of Howard Gould in New York State produced a number of excellent records, one cow—Slane Clara—having a record of 9046 pounds, testing 4.26 percent fat. Dexter milk averages about 4 percent fat.”

— The American Kerry and Dexter Cattle Herd Book, Vol. 3 (1918–1919). Published by the American Kerry and Dexter Cattle Club, New York. Public Domain – historical agricultural record.

Historical Note:

These figures summarize the first official Irish milk tests (1916–1917), supervised by the Department of Agriculture and Technical Instruction for Ireland. The original test ledgers are not digitized, but this printed record remains the only publicly available summary of those results — making it the earliest documented production data for the Dexter breed.

It’s worth noting that those results were only possible because the cows were milked under strict supervision — not while calf sharing. Accurate data and calf sharing simply don’t mix, and the early breeders knew it. They measured to learn, not to guess.

Reconnecting Past and Present

The 1916–1917 Irish Dexter milk tests measured lactations ranging from 33 to 45 weeks — roughly 230 to 315 days. The longest-milked cows produced over 8,000 pounds of milk, while the average Dexter gave between 4,500 and 6,000 pounds — steady, family-sized production from cows managed with ordinary care. Those records didn’t specify what lactation the cows were in, but it’s likely that many were mature milkers well past their first or second calves. A Dexter’s best years are often her fourth and fifth lactations — proof that good breeding rewards patience.

My own lactations are intentionally shorter — about 200 to 215 days — because I dry cows off when their production drops below 4 pounds per milking. At that point, the feed they receive during milking costs more than the milk is worth. That isn’t stinginess; it’s stewardship. Historical farmers made those same decisions, watching the bottom line while protecting the health of both cow and pasture.

Even with those shorter cycles, my cows hold their own beside their heritage counterparts:

-

Carly, in her second lactation, produced 3,976 pounds (≈462 gallons) over just 214 days — comparable to the lower end of the Irish test cows once adjusted for time.

-

Tilly, one of my smallest cows, in her second lactation produced 3,005 pounds (≈349 gallons) over 199 days — remarkable efficiency for her size and thrift.

And they’re only getting started. If the old rule of thumb still holds — that production climbs steadily through the fourth or fifth lactation — my girls are right on track to meet those historical records head-on.

Measured honestly and managed sensibly, today’s Dexters still echo the same principles that once defined the breed: thrift, balance, and purpose. Industrial agriculture might chase extremes, but heritage breeders like me still aim for what our predecessors valued most — cows that serve the family, the pasture, and the future.

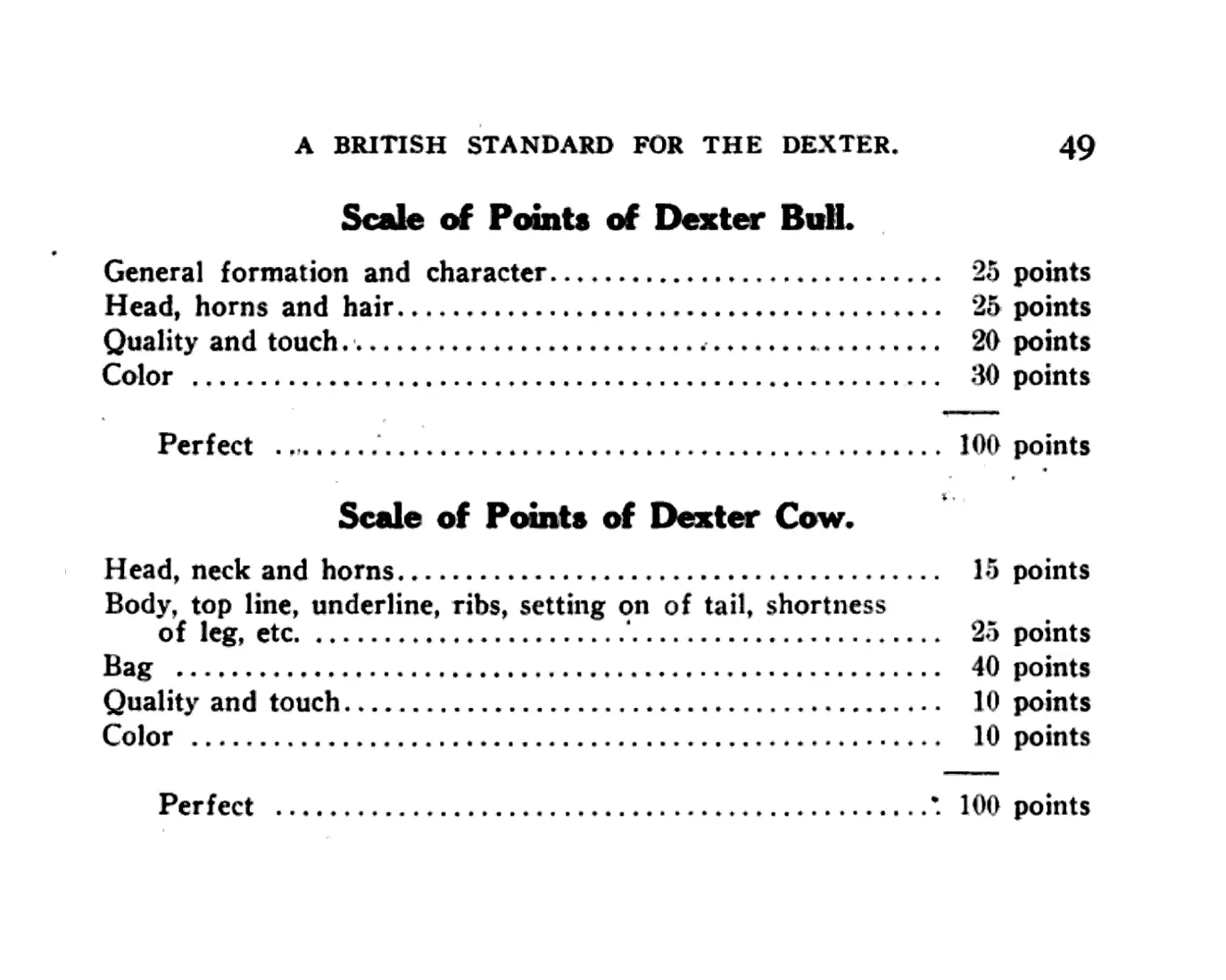

Fun Fact:

In the earliest written Dexter breed standards, udder quality carried the most weight of any single trait — worth 40 out of 100 total points in the evaluation of a Dexter cow. By comparison, body conformation earned just 25, and color only 10.

Early breeders clearly understood what made a good family cow: steady temperament, balanced structure, and a sound, productive udder that could nourish both calf and household. Long before milk meters and spreadsheets, they measured what mattered.

“Bag — 40 points. Body, top line, underline, ribs, setting on of tail, shortness of leg, etc. — 25 points.”

Source: A British Standard for the Dexter, in The American Kerry and Dexter Cattle Herd Book, Vol. 3 (circa 1918–1919). Public Domain — digitized historical record.

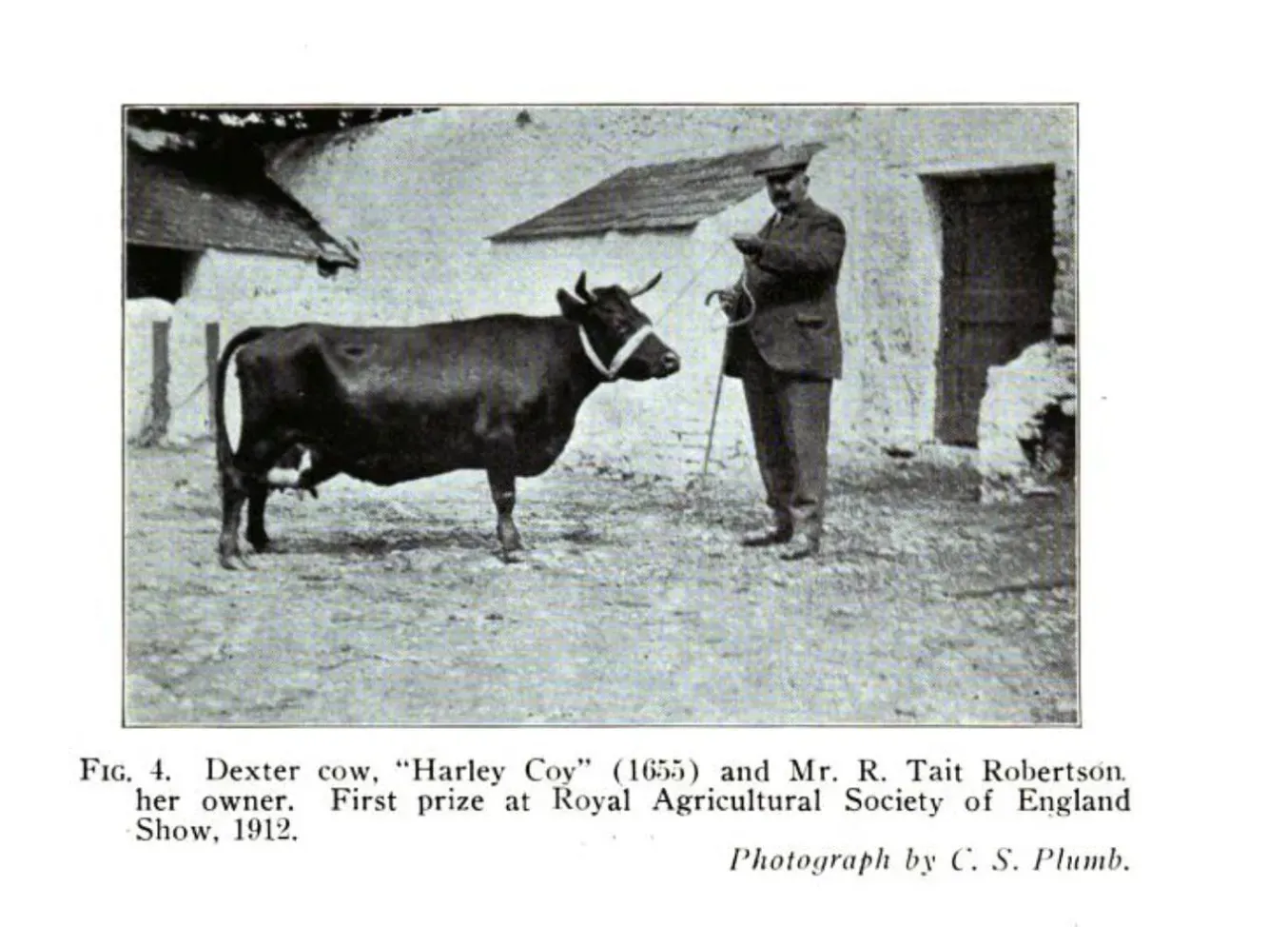

Harley Coy (1655) — A Model of Dexter Type

Photographed by C. S. Plumb, this Dexter cow, Harley Coy (1655), won First Prize at the Royal Agricultural Society of England Show in 1912. Owned by R. Tait Robertson, she represents the kind of balance early breeders valued — deep-bodied, sound-footed, and with an udder built for function as much as form.

Source: A British Standard for the Dexter, The American Kerry and Dexter Cattle Herd Book, Vol. 3 (1918–1919). Public Domain – historical agricultural record.*

You don’t get a cow like Harley Coy without effort.

She was the result of generations of disciplined, data-driven breeding — not luck. Every choice her breeder made was intentional: balance over bulk, function over flash.

Is she perfect? Of course not — there’s no such thing as a perfect cow. But how many modern Dexters even come close?

As breeders, we’ve gotten lazy.

We’ve mistaken registration papers for progress and proof of worth. Nothing could be farther from the truth.

The blueprint of the ideal Dexter still exists — in old herd books, milk records, and photographs like this one. What was built through stewardship can be rebuilt the same way: with patience, data, and devotion.

Big Ag Changed the"Why"

© Nigel Cattlin / Alamy Stock Photo (Image ID: BDJG2Y). Licensed for digital publication.

Big Ag didn’t invent record-keeping; it redefined its purpose.

The early record books of agriculture were built on stewardship — a desire to understand and improve. When farming scaled into industry, the motive shifted. The same tools that once protected diversity and resilience were repurposed to chase uniformity and yield.

Where heritage Dexter breeders tracked height, growth rates, and milk weights to strengthen families and bloodlines, industrial dairies tracked gallons and inputs to strengthen quarterly reports.

The goal moved from better cows to more milk.

From balanced herds to bigger numbers.

That shift changed everything — not just how cattle were bred, but how they were valued. The cow became a unit of production rather than a living creature within a system of care. Breeding decisions moved from the barn to the boardroom — made by analysts instead of stockmen.

In time, the results began to show.

High-output breeds were pushed so far that many can no longer thrive without constant human intervention — grain-heavy rations, specialized housing, and tightly managed breeding cycles.

Dexters never followed that path.

Their smaller size, thriftiness, and strong maternal instincts remain proof that resilience can’t be engineered; it must be preserved.

The tools themselves aren’t to blame. A scale isn’t industrial. A spreadsheet isn’t unethical. The difference lies in the motive behind the measurement.

When we use data to serve the animal and the land, it’s stewardship.

When we use data to serve only the bottom line, it’s exploitation.

Bringing the Practice Home Again

Modern homesteads have the chance to continue the careful habits that existed long before industrial agriculture. We don’t need massive herds or corporate budgets to make meaningful progress — just good records, good instincts, and honest work.

The principles that once built strong herds still work today:

-

Keep detailed records — because memory fades, but data enlightens.

-

Pair animals thoughtfully — breeding for health, balance, and temperament, not just output.

-

Share the truth openly — transparency rebuilds the trust that “profit above all” once broke.

These aren’t industrial habits — they’re stewardship habits, and they’ve always belonged to small family farms.

A heritage-bred Dexter cow doesn’t need a corporation to define her worth. Her value is written in her steadiness, her thrift, and her ability to raise a calf and provide milk for her family on good grass and common sense.

When small farms track data with purpose, test with integrity, and breed with vision, We aren’t chasing industry’s methods — we’re keeping alive the wisdom of those who stewarded the Dexter breed generations before us.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why do heritage Dexter breeders track so many traits?

What’s the difference between heritage and modern breeding programs?

How does milk testing fit into whole-herd selection?

Do heritage Dexters still make good beef animals?

Why is temperament part of selective breeding?

What traits signal a well-balanced Dexter cow?

Can small farms really maintain data like big dairies do?

How do I choose a Dexter bull for a milk-focused herd?

Are polled Dexters OK for milking and breeding?

The “Why” Still Matters

The heart of good farming has never changed. The tools evolve — paper ledgers become spreadsheets, and milk pails give way to digital scales — but the purpose behind them is still ours to choose.

Big Ag borrowed the methods but lost the intent.

When we measure for profit, we lose the balance of the animal.

When we measure for stewardship, we restore and refine it.

Every record written, every test run, every pairing considered with care — it all adds up to something larger than data. It becomes a legacy of responsibility and proof that small family farms can lead with both tradition and truth.

Because every number tells a story — not just of milk and calves, but of a unique breed and a cherished way of life worth preserving.

At the end of the day, keeping records in a small operation like a homestead isn't about mimicking Big Ag. It's about reclaiming the wisdom of those who came before us -- the breeders who understood that data was not a corporate invention, but a farmer's tool for stewardship.

Continue Reading

- Dexter Cattle — heritage type, conformation, and bloodlines

- Dexter Raw Milk — testing and milk weights

- How I Raise My Dexter Calves — the management side of sustainable breeding

- Why I Don’t Calf Share — where ethics and milk testing meet